Why Tech Professionals Are Upskilling with Drone Survey & Mapping Certifications?

Not just India, but the entire world has entered a new era in the tech industry today, where software development, data analytics, and

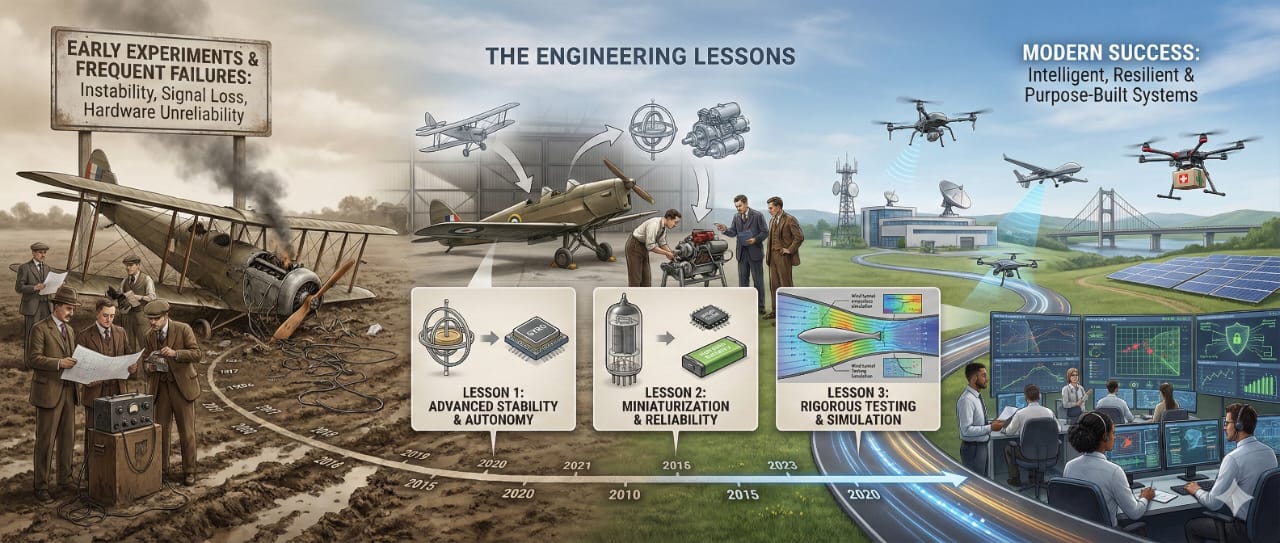

In the early days of drone development, there were many failures across various aspects. The early drones had limited processing power, low battery capacity, unreliable sensors, and fragile regulatory frameworks, leading to frequent accidents and breakdowns. Each failure reformed drone engineering practices. It is important to cope with early failures to understand how drone engineering has evolved and how drones have evolved from failures and are turning out to be magical machines for commercial uses.

Formerly, drones were mainly used for military purposes. With the advancement of technology in the late 1990s and early 2000s, smaller components emerged and brought about a revolution of sorts. Many early drones had minimal redundancy, single-point dependencies, and optimistic assumptions about operating environments. Commercial drones in the 2010s further exposed these weaknesses. The following incidents highlighted that success in controlled conditions did not guarantee consistency.

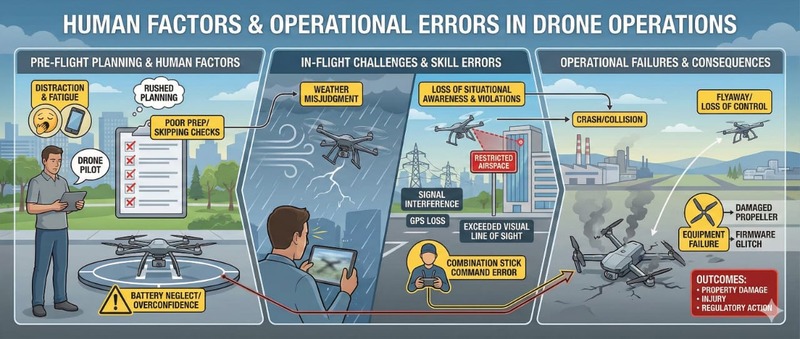

Power-system instability was one of the early sources of drone failure. Early lithium-polymer batteries were often overdischarged, exposed to extreme temperatures, and suffered mechanical damage. Insufficient battery monitoring caused voltage collapse during operation, leading to crashes.

Structural failures were also common when lightweight frames were unable to withstand repeated vibration, minor impacts or gust loads. These occurrences necessitated power management and structural testing under realistic conditions. Consequently, contemporary drones have battery management systems, redundant power paths, and modular airframes for providing enhanced fatigue resistance and ease of repair.

Early flight controllers hinged on basic inertial measurement units and simplistic control algorithms. Sensor noise, calibration errors and limited processing power caused instability, oscillations and unpredictable behaviour, mostly during hovering or descent.

Navigation failures were common when GPS signals degraded or became unavailable. These inadequacies forced engineers to adopt sensor fusion techniques that combine inertial data with barometric, magnetic, visual, and satellite inputs. The expansion of robust state-estimation algorithms significantly enhanced stability and allowed support when individual sensors failed.

Communication loss between the drone and the operator was one of the most concerning early failure modes of drones. These failures highlighted the importance of deterministic failsafe behaviour. Design systems that can assess link quality and initiate predefined responses, rather than relying on optimistic reconnection attempts.

With smart and connected drones becoming more common due to technological advancements, security concerns also came hand in hand. Early drones were easily intercepted or spoofed attributable to the lack of countermeasures. GPS manipulation demonstrated that drones could be misled into incorrect positioning, pinpointing a major weakness.

These occurrences transformed cybersecurity into a core engineering requirement. Modern drones are equipped with encrypted communication links, authenticated firmware updates and anomaly-detection mechanisms comparing multiple navigation sources to identify cases of spoofing or jamming.

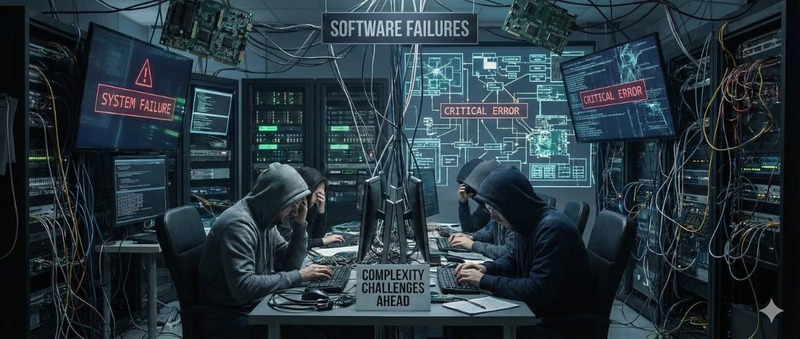

Software was a failure-prone component of early drones. Open-source flight stacks improved innovation but also introduced integration challenges and regression bugs.

Firmware updates often brought about new failures. These experiences underlined the necessity for disciplined software engineering practices, for example, version control, automated testing and simulation-based validation. Hardware-in-the-loop and software-in-the-loop testing environments were important tools allowing engineers to assess failures without risking physical assets.

Several incidents were the result of human error. And not of any technical glitch. Misjudgment of battery life, misunderstanding of flight models or ignoring environmental constraints. These issues highlighted the implications of human-centred design. Engineers simplified user interfaces and implementing beginner modes that constrained performance until suitable experience was demonstrated. Training programs for commercial operators also advanced with time and the advent of modern drones.

Regulatory lag behind technological progress generates uncertainty and inconsistent operating standards. When no clear guidelines were laid down, engineers focused mainly on performance and not on compliance or traceability.

Major incidents of drone accidents prompted regulatory bodies to take more accountability for the incidents. This shift triggered engineering advances, leading to the inclusion of remote identification, immutable flight logs and standardized safety features. Engagement between manufacturers and regulators became important to align with technical competencies and societal expectations.

The effect of early failures changed drone engineering significantly. Redundancy and fault tolerance replaced minimalism as guiding principles, verification and validation processes were prolonged to include environmental extremes, deliberate signal loss, and simulated component failures. Telemetry and data logging are important in post-incident analysis and incessant improvement of drone systems.

The early failures in drone systems led to improvements in reliability, endurance and safety. Contemporary drones are more consistent and are better to deal with accidents. Though challenges still exist, mainly in urban environments. With more and more sectors becoming inclined towards the use of drones, innovation and betterment of these devices is a certainty, to say the least.

By examining the early drone failures, engineers developed resilient architectures, rigorous testing methodologies and safer operative frameworks. Modern drones indicate a significant progress in intricate systems. As an alternative, it is built through experimentation, failure and refinement. The continuing lesson for engineers is clear: embracing failure as a source of learning is essential to building reliable drone systems.

If you want to become a trained drone pilot and want to open a new avenue, you can always come to us at FlapOne Aviation and turn your dreams into reality.

Our experts can help assess your needs and suggest the right drone services for your industry.